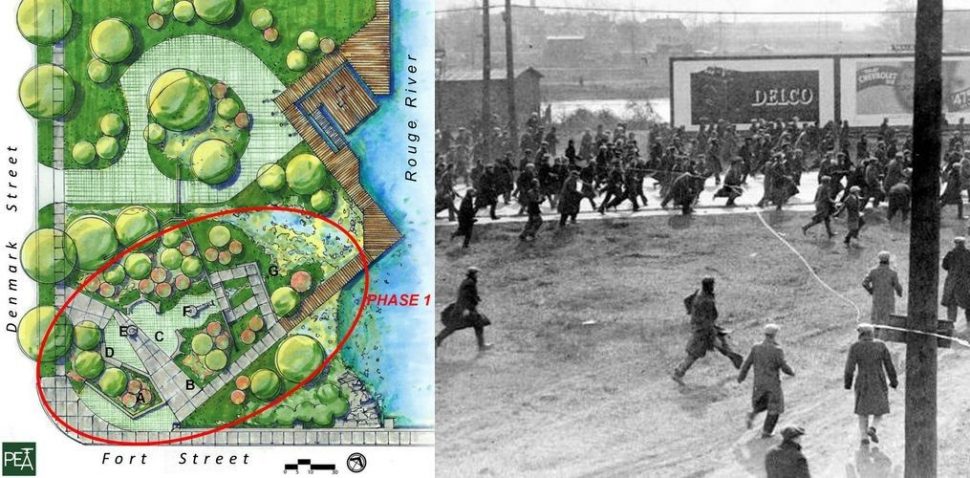

Plans for what will be Detroit’s newest park call for plenty of trees and gardens, walkways and reflection pools, even a kayak launch. In all, the plans appear serene and peaceful, a respite from the surrounding industrialization, though the event that the park is intended to commemorate was anything but: one of the bloodier confrontations in Detroit labor history and one of the triggers for the unionization of the auto industry.

Images via MotorCities National Heritage Area, Walter P. Reuther Library.

The organizers of the 1932 Ford Hunger March, by many reports, didn’t intend for their demonstration to erupt in violence. Instead, unemployed auto workers – many of them laid off from Ford’s massive River Rouge plant at a time when unemployment insurance and welfare were nonexistent or scarce – wanted to communicate their plight to Henry Ford himself, figuring that in exchange for making millions off their labor he should take care of his workers.

By March of 1932, worker frustrations mounted in Detroit. Hunger Marches in other cities had brought the issue of unemployment to public consciousness and the Detroit Unemployed Council, an arm of the Communist Party of the United States, decided to organize a Hunger March on River Rouge to ultimately present to Henry Ford a list of 14 demands. Among those demands: two 15-minute rest periods, seven-hour work days, no more work speedups, the abolition of the Harry Bennett-led Service Department and its staff of thugs, the end of racial discrimination at Ford, and the right to organize.

The march would take place on March 7. Estimates placed the crowd’s size at 3,000 to 5,000 people, bolstered by men laid off from Ford that morning, according to some reports. After a plea from march leader Albert Goetz to remain nonviolent, the marchers headed east from the Oakwood Heights neighborhood, across the Fort Street bridge, and then north along the Rouge River toward the Dearborn city limits. There they met a contingent of Dearborn police who then fired tear gas into the crowd when the marchers refused to turn around.

Demonstrators prior to the Hunger March. Photo courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library.

In response, the marchers picked up rocks from a nearby field and began throwing them at the police as they continued to advance toward the Ford plant. They made it as far as an overpass by the plant’s entrance before the Dearborn Fire Department turned its hoses on the crowd. Dearborn police, along with Ford’s police department and Bennett, began shooting into the crowd, killing four men and wounding dozens more.

The marchers retreated, but five days later – after attempts by both sides of the conflict to commandeer the narrative of the conflict in the press – the organizers of the march staged a funeral procession for the four who died (a fifth died from his injuries three months afterward) that attracted anywhere from 25,000 to 60,000 people.

Demonstrators at the funeral procession. Photo courtesy Walter P. Reuther Library.

While the 1932 Ford Hunger March didn’t directly lead to auto industry unionization, the killings – and the subsequent funeral procession – received national press coverage and helped to change attitudes about organized labor during the Depression, the latter a factor in the 1932 election of Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose New Deal policies made unionization easier. GM and Chrysler eventually recognized the United Auto Workers in 1937, but Ford – bolstered by Bennett’s union-busting violence – held out until 1941.

The concept of a commemoration to the Hunger March in the Fort Street Bridge Park came from the recent replacement of the bridge itself, which had a historic site plaque mounted to it. According to Brian Yopp, director of programs and operations for the MotorCities National Heritage Area, the plaque referenced events that happened on the old bridge, so without that bridge in existence, the historical marker had to be decommissioned.

“There’s not a lot of recognition for the Hunger March here in Detroit because of its implications and because it’s hard to figure out who holds the ball for it,” Yopp said. “Even though it predates them, the UAW local have been the ones to carry the banner for the march. And on the flip side, Ford doesn’t want to look at it as a celebratory event.”

Ford has, however, showed some support for the project, mostly by storing materials from the deconstructed Fort Street Bridge, Yopp said.

The Fort Street Bridge Park, a project of the Fort-Rouge Gateway Partnership and MotorCities National Heritage Area, aims to transform a block of urban residential land on the west side of the Rouge River, at the base of the newly renovated Fort Street Bridge, into “an experiential green gateway” with interpretive signage on the Hunger March and meeting spaces similar to those that helped launch the march.

Construction of the first phase of the park, which is contingent on the success of a $10,000 fundraising campaign, is scheduled to take place next summer.

Recent Comments