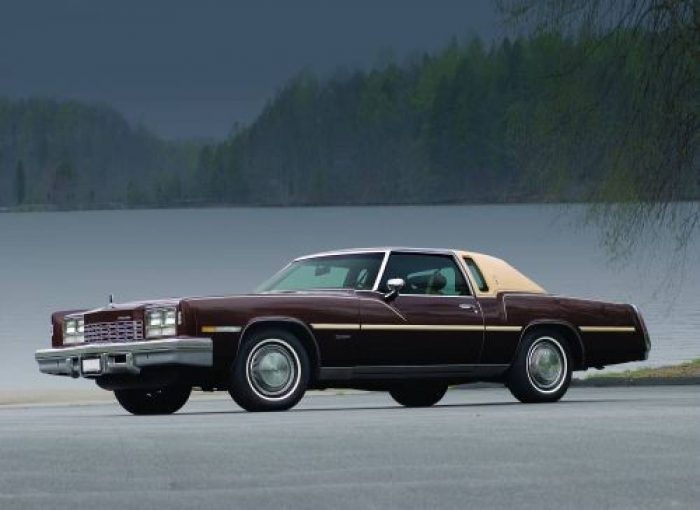

Probably because, in the repetitious void that such journalism represented, the 1977 Oldsmobile Toronado Brougham represented a target too easy for the magazine bullies to ignore, the most obvious of the proverbial low-hanging fruit. Go on, admit it. If you were coming of age as an automobile enthusiast during the 1970s, and were leaving sweaty fingerprints on the road-test monthlies within days after they were printed, you almost certainly read something nasty about this car, someplace.

It’s possible that the naysayers were banging down Kool-Aid that had been carefully blended on the 14th floor of General Motors headquarters before the move to the RenCen. Mammoth changes were going on at the General that year: It was the first year for GM’s radical, post-OPEC slimming of the real mammoths, its full-size automotive line. More than 30 years later, it’s still a challenge to describe how shocking this transformation really was. In one new-car rollout, GM veered sharply away from a half-century of Sloanist growth as measured by wheelbase and curb poundage.

It was amazing when it happened. The B-body titans immediately dropped eight inches of wheelbase and, on average, about 800 pounds. The sharp-angled replacements weren’t tiny, still measuring 116 inches between the hub centers, but still–it was a dramatic shrinking. When everything stopped spinning, GM’s E-bodies, which included the Toronado Brougham and wraparound-backlite XS, became the biggies by default, and they were. Riding on a 122-inch wheelbase with even a base model weighing in at more than 4,600 porcine pounds, this was not exactly the Purplesaurus Rex that GM was trying to serve. But Oldsmobile still enjoyed its first million-unit sales year in 1977, producing just over 33,000 Toronados.

It’s not too hard to see why–for all their comparative size, the Toronados were well-styled. At least of couple of these beautiful E-body cars found their way into Ray Wallace’s family when he was a young engineer in his 30s. Now 62, he is part of an undeclared minority audience that appreciates Seventies cars enough to buy them, appreciate and drive them lustily. And it’s not just Oldsmobiles he adores, either. There’s an all-original De Lorean DMC-12 in his garage. Plus, he’s just acquired a 1976 Cadillac Eldorado convertible. They, like this Toronado Brougham, are regularly driven.

The Oldsmobile had about 9,000 miles when he bought it, and he’s since added about 2,000 more miles. Ray is savvy enough to describe 1977 as “a transitional year for these cars. By then, you couldn’t get a 455 in them anymore. Oldsmobile went to its own smaller engine, the 403-cu.in. V-8, to see if it would work in them. I read an article somewhere that if the 403 worked, they’d be satisfied with it for the 1978 model lineup.”

And work it did, especially in conjunction with the Toronado’s general design. The Toronado Brougham is a classic from the Seventies with clear Classic overtones. The 1977 version was the penultimate year of a body style and wheelbase that looks almost Colonnade, but actually debuted in 1971, the Toronado’s first full redesign. By 1977, the line had grown to two models, and nearly three–the Toronado XSR, designed with power-retractable glass T-top panels, never made it beyond running-prototype stage. Come 1980, the E-body cars shrank down to 114 inches of wheelbase, the front-drive platform now very similar to that of the K-body Cadillac Seville. The smaller cars used space better than this one: The distance encompassing the water pump, fan shroud and grille is enormous, and essentially wasted. So is half the trunk, thanks to a leaned-over spare beneath the rear window.

1977’s Toronado is Oldsmobile to the core, though. That 403 is an Olds-designed powerplant, and to correct a sometime misconception, it’s not a variation on the 400-cu.in. V-8 that Oldsmobile debuted in 1965. The 400 is considered a big-block because of its 10.625-inch deck height. The 403, on the other hand, is a resized derivative of the Olds 350 small-block from 1968. Both engines share the same 3.385-inch stroke, but the 403’s bore of 4.351 inches is the largest of any Oldsmobile small-block. This is the same 403 that found its way into the California-market Pontiac Trans Am beginning in 1977. It’s a reliable performer, if unspectacular, rated at 185hp and bolted to a standard three-speed automatic.

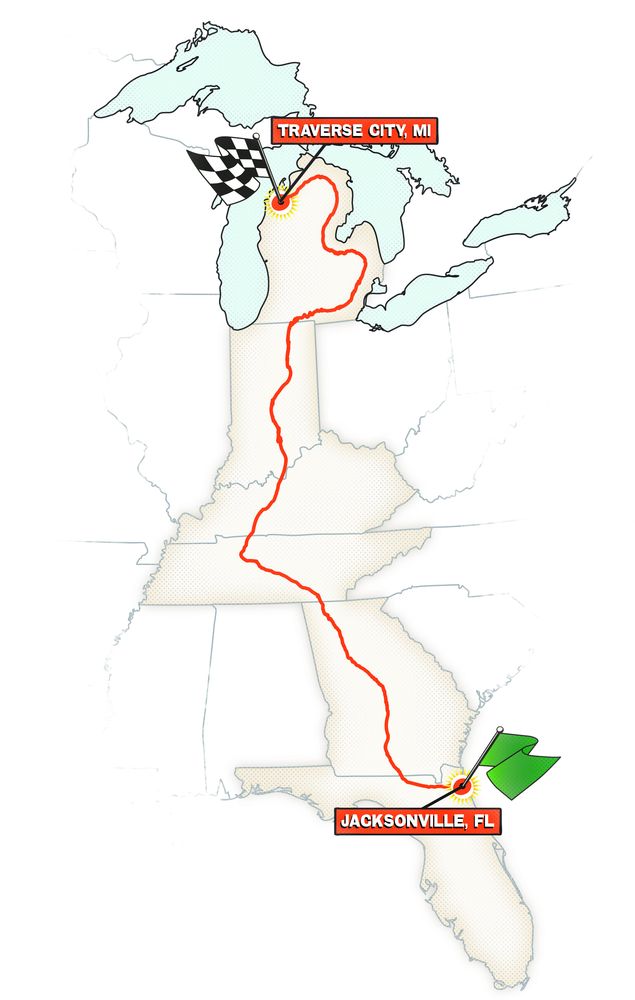

So when Ray refers to this as a “luxury sport car,” the statement needs to be filtered through a Me Decade kaleidoscopic viewfinder. That was when true driving technologies like fully independent suspension didn’t exist for most people, who didn’t care anyway. “The car, with no front driveline hump, was made for somebody six-foot-four with long legs, who wanted to go pretty fast. Not from a standing start, of course–but once you get over 60 MPH and up to 100, it just glides. I bought it on a Friday and drove it back to my home in North Carolina. I don’t think we were ever under 80 MPH the whole way home. You hit something in the road at that speed and it just glides over it; it doesn’t bounce.”

“It also represents the last of the really big, long-nose cars,” Ray continued. “You know, on the inside, they’re really not that big: really large front seats, but really tiny back seats. They’re very luxurious, though, and they just cruised, just floated along. I’ve always liked that.”

Ray is this Toronado Brougham’s second owner. It came from a friend’s family, having been sold new in Indianapolis as a 1977 leftover, after an early life as a dealer demonstrator. To see it, you’d think it’s a new car, even when you inhale, because the original owner never smoked. Truthfully, he never did much of anything with the Oldsmobile except slip it out for relatively short runs. But the car did get driven fairly consistently, thus avoiding the dried-out rubber and leaky gaskets that plague any number of cars bought new to put in a Ziploc.

Those first trips bordered on the obsessive: “The original owner took it out two or three times every day, just to run it, even if it was just once around the block. Eventually, it got to the point where he almost wore out the keys, because the keys were really thin. I had to be real careful when I first got the Olds because the keys were so worn, and had new ones made. It never sat for a long time because he always started it. Nothing leaks.”

When Ray went to buy the Toronado, it had been sitting outside for two years after the death of the original owner. Leaves were matted against the paintwork. Ray worried, anticipating any number of problems, until he drove it and saw for himself how beautifully it performed.

Returning the car to its former glory wasn’t hard. It took only a few brushstrokes of touch-up paint to remedy the decomposing finish; the halo vinyl roof spiffed up with much less effort than Ray was anticipating. “It came back beautiful. I used one of the old stiff-bristle brushes, and started out with some really mild soap to see how it would clean up. After that, I used a real good vinyl-top cleaner with a little buffing pad, and then put vinyl-top treatment on it every week for about six weeks, and the top’s condition just came back perfectly.”

Ray is a retired facility and manufacuring engineer for Timken who’s also worked with Penske Racing, so he’s a car guy to the core, and knows something about how the masses and the media both viewed big American iron when this Oldsmobile was new. None of that condescension daunts him.

“Yeah, I know what you’re talking about,” he mused. “I wouldn’t run right out and buy one of these any more than I’d buy any Seventies car. But if you’ve got one that hasn’t been abused, or hasn’t been in an accident, a Seventies car was made to last for a long time. There’s still a bunch of people who specialize in rebuilding these old front-drive transmissions from the Eldorado and Toronado.

“If you think you’re going to drive something forever and never have any problems, you shouldn’t buy any car. You’ve got to accept it. I wouldn’t be afraid to buy a Toronado, though,” he explained. “I guess one point I’d make is that, when I graduated from high school in 1965, nobody wanted the early Fifties Chevrolets and Fords. You could get a 1946 to 1954 Chevrolet, I remember, for 50 bucks. Everybody wanted a 1955, ’56 or ’57 Chevy, and they were expensive. The junkyards in Ohio where I grew up were full of ’49 and ’54 Fords for 75 bucks each–just full of them.

“The cars from the Seventies are in the same place now. I’ll tell you, though, you go to a car show and you’re starting to see a lot of them.”

Club Scene

Toronado Owners Association

P.O. Box 373

Hubertus, Wisconsin 53033-0373

www.toronado.org

Dues: $30/year Membership: 475

This article originally appeared in the January, 2010 issue of Hemmings Classic Car.

Recent Comments